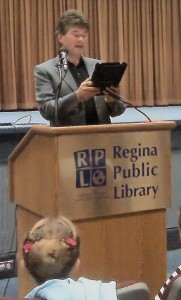

From last September through May of this year, I served as writer-in-residence at the Regina Public Library, the latest in a long string of writers to serve in that position, which I understand is the longest-running program of its kind in any library in the country.

From last September through May of this year, I served as writer-in-residence at the Regina Public Library, the latest in a long string of writers to serve in that position, which I understand is the longest-running program of its kind in any library in the country.

During my nine months, spending one day a week in my library office, I met with 75 individual writers, many more than once, some several times, critiquing their writing and answering their questions.

And what, you may ask (or you may not, but I’m going to imagine you did so I have a reason to continue this post), was the writing advice I found myself dispensing over and over again during those nine months? And was there anything I didn’t tell them I possibly should have?

I’m glad I imagined you asked that. Let me enumerate, beginning with what I did tell them:

1. Your writing is not perfect. Don’t feel bad, my writing isn’t perfect either. Nobody’s writing is perfect. It can always be improved. Presumably that’s why you came to the writer-in-residence, in the hope of improving your writing.

This may seem obvious, but there were a couple of individuals I met with who seemed quite shocked at the number of flaws I found in my reading of their writing. They thought what they had shown me was essentially ready to be published, and what they were really looking for was confirmation of that belief. When I told them I felt otherwise, and showed them their heavily marked-up manuscript, they were taken aback, and in a couple of cases visibly upset.

It’s an understandable reaction, especially if (as in these instances) you’ve literally worked for years on the piece of writing in question. But it’s something we’ve all had to learn: those hundreds of hours you put into writing your, say, epic fantasy may ultimately result in…nothing. Not even a pile of paper, in these digital days. (Of course, these digital days also mean that, even if no publisher under the sun will give your work the time of day, you can still self-publish it, and you might even find a few readers that way, so there’s that; but more likely it will be as unloved and unread in digital form as it would if you had mimeographed it and were trying to hand-sell it by standing on street corners yelling at passersby.)

Pretty much all of us published writers also have books that we labored over that went nowhere. You know what you do? You write another book. And another one after that. And another after that. Until either one of them does go somewhere, or you get fed up and quit.

As Stephen King (I believe), said, “Anyone who can be discouraged from writing should be.” But those who can’t, who carry on anyway, are the ones most likely to eventually succeed…well, for some definitions of the word “succeed,” but that’s a topic for another post.

2. There are things you can fix. Here are some. Fixing them won’t result in perfection (there is no such thing), but may inch you a little closer to it.

a) Show, don’t tell. I know, it’s a hoary cliché, but it’s also excellent advice. And it covers off a lot of writing flaws. “Sam opened the door and walked into the throne room,” is telling us what happened, “Sam pushed at the massive bronze doors. Slowly they swung open, groaning, as though in despair at having to allow someone so insignificant into the gleaming marble magnificence of the throne room beyond,” is more in the line of showing. It’s the difference between descriptions and action that lie flat on the page and those that leap off the page and beat the reader about the head and shoulders with the flat of a sword. So to speak.

b) While keeping in mind a), don’t show us everything. Choosing which scenes to dramatize, which ones are needed to advance the plot or develop the characters, and which can be sloughed over, is one of your basic tasks as a writer. It’s rarely necessary, for example, to fully dramatize the scene where the characters wakes up, gets out of bed, uses the toilet and brushes his teeth (unless something vital to the plot happens during those mundane actions). It usually suffices to say, “Next morning Sam made his way to the throne room,” and then go on to dramatize what happens in the throne room. Dramatizing scenes that don’t need it slows the story and bores the reader.

The opposite flaw, of failing to dramatize scenes that really need to be dramatized, typically both bores (because those scenes are the ones where the real drama and action of the story are found) and confuses (because he or she may have missed something vital to understanding the tale, his or her eyes having slid right over the non-dramatized-and-therefore-not-obviously important scene) the reader. (Also, as an aside: don’t [as I just did {and probably too often do}] use too many parenthetical statements.)

c) Watch out for the passive voice. “Was” and “were,” etc., have their place, but often you can liven up your text by restructuring sentences to avoid them. Rather than, “The sky was clouding over,” write, “Long gray streamers of cloud slipped silently across the sky, smothering the stars one by one.” I usually do a pass through my manuscripts using the Search function to find all instances of “was” and “were” and other passive verbs, just to see if there are places where I can punch up the language a bit.

As well, often passive voice is a flag that you are, per a), telling, not showing. “Sam was amazed at how big the throne was and how little the King was.” “Sam gaped, amazed, at the gold-plated chair, twice his height and studded with rubies—and at the elfin figure of the King perched like a child upon its vast seat, legs sticking straight out in front of him.”

d) Watch out for adverbs. Yes, it’s another writing-advice cliché, and yes, adverbs do have their uses, but “Sam ran quickly from the throne room” is rarely as interesting as “Sam scuttled for the door like a kitchen cockroach caught in the beam of a flashlight.”

e) Be specific. Don’t tell us something smelled nice, tell us it smelled like a mixture of fresh-baked bread and roasting coffee. It’s really just another variation of show, don’t tell. Specific sensory details add to the effectiveness of scene descriptions. Generic details are the equivalent of badly painted rickety flats on an under-lit stage; specific details are like Hollywood-quality sets from the days when they couldn’t fill in the empty spaces with CGI.

f) Spelling and grammar matter. Nothing will lose you an editor’s attention faster than the revelation (which usually comes on the first page) that you don’t actually know how to punctuate dialogue, how to spell “somnambulist” (and the title of your book is The Somnambulist), or understand the importance of subject-verb agreement or the correct use of apostrophes (hint: it’s not to turn a noun plural). You wouldn’t trust a carpenter who can’t drive a nail; why should you trust a writer who can’t place apostrophes?

3. The only way to get better is to write more. Half a million words is one oft-referenced threshold that one must churn out before one writes at a professional level. I’m sure I wrote more than that before I started getting published. But the thing was, I kept writing. Three novels in high school. Half a dozen more before I sold even a short story. Always writing, always sending out what I had written, always moving on to something else. The number of hours involved and the amount of sitting and typing and postage that entailed is mind-boggling in retrospect. The endless series of rejection letters was disheartening. But I didn’t quit. I wanted to be a writer…and whaddya know, now I is one.

4. But there are no guarantees. You may write your half a million words or more…and never get better. And actually this is one thing I didn’t typically tell the writers who came to me while I was writer-in-residence, because my job was to en- not dis- courage.

I think there is actually a…call it a knack, for want of a better word…for writing, for being able to put words together in an interesting fashion and tell a tale thereby. Maybe it’s genetic. Maybe it’s environmental, picked up through the reading of many books as a child. Whatever it is, some people seem to have it, and some don’t; and while perhaps some of those who don’t can learn it, others, sadly and clearly, cannot. They may write their whole lives and never advance beyond a certain level. Their prose remains clumsy, their action scenes lifeless, their characters flat, their plots uninteresting. They may turn out their half a million words only to find that a disinterested reader can tell no difference in quality between what they wrote at the beginning of that monumental undertaking and at the end of it.

That may sound depressing. Heck, it is depressing. But there is one thing about it: those who do not have the knack for writing are rarely those who can be discouraged from it. And there are other reasons to write besides publication. Plenty of people write only for themselves, because they enjoy it, just as plenty of people who paint paintings that will never be hung anywhere but in their own homes, plenty of people collect stamps, plenty of people pick pickled peppers. Writing can be an avocation as well as a vocation (and even, sometimes, a vacation, if you have a full-time job and all you really want to do is write; also an invocation, if you’re of a mystical bent…but I digress).

So forget I said anything about some people not having the knack for writing. I’m sure that doesn’t apply to you. All you need to do is keep beavering away, writing writing writing, striving to make everything you write the best it can be and the thing you write after that even better, and some glorious day you, too, may see your byline on a published work…

And the thrill will last about two minutes, and then you’ll have to get back to writing.

As screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan puts it, “Being a writer is like having homework every day for the rest of your life.”

But at least this assignment is done.