Alex Mitchell doesn’t have the slightest interest in the auction his mother drags him to after a disastrous day at junior high. Antiques are her interest, not his—yet somehow, when they head home, he’s the one clutching a Civil War bugle. When Alex blows the horn, he sets in motion a train of events that will destroy his home town of Oak Bluff, Arkansas…unless he can figure out the secret of the haunted horn in time, and, with the help of his new friend Annie Parker, evade the gang of bullies out to get him, her, and the haunted horn.

Alex Mitchell doesn’t have the slightest interest in the auction his mother drags him to after a disastrous day at junior high. Antiques are her interest, not his—yet somehow, when they head home, he’s the one clutching a Civil War bugle. When Alex blows the horn, he sets in motion a train of events that will destroy his home town of Oak Bluff, Arkansas…unless he can figure out the secret of the haunted horn in time, and, with the help of his new friend Annie Parker, evade the gang of bullies out to get him, her, and the haunted horn.

Available only on Kindle for $2.99.

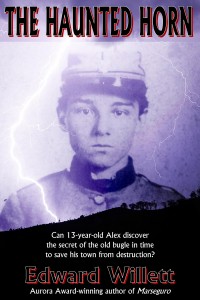

The Haunted Horn

By Edward Willett

Chapter One: The Old Bugle

Alex Mitchell first saw the old bugle late one Friday—a Friday so miserable he later thought he should have taken it as an omen.

He’d started the day by being late to class; not just any class, but “Iron Head” McCullough’s science class. It was his mother’s fault—she’d lost her car keys again—but try explaining that to Iron Head. Being lectured at the front of the room in front of everybody else wasn’t made any easier to take by the fact he had the best grades in the class, and everyone knew it. By one of Edmund Kirby-Smith Junior High School’s myriad unwritten laws, that meant his classmates hated him whenever they were in the science lab.

Maybe jealous science students were responsible for the further decline of his fortunes in second-period physical education. As usual, he’d been the last one chosen for basketball (something he was used to, being, in his father’s words, only slightly taller than a fire hydrant) and then someone had hidden his clothes while he was in the shower. By the time he’d found them, rolled in a ball and stuffed in the wastepaper basket in the toilet, the Grade 7 boys who had P.E. next were already coming into the locker room, and had been greatly entertained by the spectacle of him trying to get dressed before the bell rang.

Of course, he hadn’t made it, which meant he had to sneak into Miss Hildebrandt’s English class in the middle of “To be or not to be…” Even though he was only the second-best student in her class, the other kids got a big kick out of seeing him raked over the coals a second time.

At lunch he spilled milk all over his French fries, in the library he caused an avalanche of old National Geographics, and in math he discovered he’d left his homework at home.

But the day reached what Alex would forever after consider his personal definition of “the absolute pits” when, going into geography class, he tripped over his own feet, flung out one hand to catch himself, and sent an elaborate toothpick model of the Great Wall of China crashing to the floor.

The room, which a moment before had been earsplittingly full of talk and laughter, fell silent in something approaching awe at the magnitude of that screw-up. The first voice to break the silence was Michael Sifton’s. “You’re dead, Mitchell,” he said from the doorway. He sounded pleased.

“It was an accident!”

“Don’t tell me. Tell the guy who made it. If you think it will do any good.”

The guy who made it? Alex knelt down and scooped up pieces of what used to Great Wall and now was only good for kindling. Glued to one of the largest surviving bits was a neatly typed card: “Sammy Findlater, Grade 8 Geography.”

Alex gulped. Sammy Findlater was every teacher’s idea of an All-American teenager. He was good-looking, always called grown-ups “sir” and “ma’am,” got terrific grades, and volunteered for every helpful task, from cleaning erasers to stapling test papers.

He was also the most feared kid on the playground, at the pool, downtown, or wherever else you had the supreme misfortune to run into him.

The teacher came in, took in the scene at a glance, and sighed. “Alex, I swear, you must have taught the proverbial bull in the china shop everything he knows.”

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Jordan, it was—”

“I know, I know, it was an accident. It always is. Well, pick up the pieces and take your seat.” She patted Alex on the shoulder as she passed. “Don’t worry about it, Alex; I’m sure Sammy will understand.”

“Oh, yeah, Sammy’s very understanding,” said Michael Sifton innocently. Alex sighed and finished collecting the no-longer-great Great Wall.

He was not surprised, as he made his way to the football field for marching band practice, to see Sifton talking to a tall, lean boy with short brown hair—Sammy. They both turned to look at Alex as he passed. He told himself it wasn’t really possible for Sammy’s eyes to be drilling holes in his head.

Nonetheless, he was relieved Sammy wasn’t waiting for him when band practice ended; even more relieved to see his mother was. All he wanted to do was climb into the familiar black Lincoln SUV, go home, and either watch TV or die—

—so of course his mother decided to take him with her to an antique auction.

Fortunately, he had ways to make such annoyances bearable. As a future best-selling novelist (he also had his sights set on the Nobel Prize in chemistry, but he figured that would take longer), he knew everything that happened to him should be grist for a story. Considering the way the day had gone, a horror story. He tried a few lines in his head.

Fallen leaves swirled crazily in the wake of the speeding car as it hurtled down the mountainside. The boy in the front seat peered morosely through the darkly tinted glass at the shadowed valley into which the car was descending, wondering where he was being taken, and why.

The thin, pale woman who had marched him from the schoolyard and shoved him into the black station wagon had said nothing. He’d had no word of explanation, but the principal had insisted that he go with her.

A shiver crept up his spine at the thought of her ice-cold touch, her burning red eyes and those too-perfect red lips. She hadn’t smiled, but he could have sworn he’d caught a glimpse of two protruding, sharp white teeth…

The woman was very quiet as she drove. He couldn’t even hear her breathing. It was almost like—like—

He turned his head and saw the steering wheel turning, the brake and accelerator going up and down, but no one in the driver’s seat…

“Honestly, Alex, I wish you’d quit sulking.”

Alex blinked and the story evaporated. Something Miss Hildebrandt had mentioned about a guy from Porlock flashed through his mind. “I wasn’t sulking.”

“Sure you weren’t—sitting there staring right through me. Alex, I’m sorry you’re going to miss Science World, but it comes on every day. This auction is only going to happen once.”

“Couldn’t Dad have come to get me?”

“Your father is busy at city hall.” His mother swung the car around a sharp corner, and Alex banged his elbow on the door handle.

He rubbed the sore place. “I hardly ever see him anymore,” he complained.

“He’s a very busy man. You know, if you let yourself, you might even enjoy this.”

“Oh, right. Dusty old furniture and faded pictures of guys with beards and funny mustaches. I can hardly wait.”

“Alex, for heaven’s sake, at least give it a chance!”

Alex slouched in his seat, arms folded.

They swept past the sign that said, “We hope you enjoyed your stay in Oak Bluff” and for several minutes followed what the locals called “the old highway” to distinguish it from the interstate that bypassed the town on the north. The road wound past stands of trees (just beginning to get serious about their autumn colors), stubble-covered fields and cozy white farmhouses. Alex watched the scenery pass and tried to resume his story, but couldn’t keep his mind on it. The trouble was, Oak Bluff, Arkansas, and its broad valley in the Ozarks foothills just weren’t dreary or menacing enough to serve as the setting of a horror story. At least, not in late October, with the leaves changing colors and the air cool and smoky. It was more like a setting for a rerun of Lassie.

Alex’s French horn case slammed against the back of his seat and only his seatbelt kept his forehead from likewise slamming against the dashboard. “They should’ve had a bigger sign,” his mother said.

He looked out his window at a small square of yellow cardboard mounted on a fence post. A red arrow pointed left. “Auction today. Three miles,” he read out loud.

His mother backed the SUV, then turned it onto a narrow road that wound up toward the valley rim. “Almost missed it!”

“Gee, that would have been terrible,” Alex muttered under his breath. At least this road looked more menacing. Unpaved, rutted, covered with leaves and overhung by the gnarled, arm-like branches of ancient oaks, it was the sort of road movie-teenagers were always venturing down prior to being sliced, diced and shredded by some chainsaw-wielding maniac in a hockey mask. Now that would be the perfect end to this day, Alex thought. He resumed his story. The driverless black station wagon (who was he kidding? He knew it was a hearse) turned off the paved road onto a rutted, weed-infested track that climbed toward a craggy mountain peak, crowned with lightning and thunder. Through ragged, storm-torn clouds, the boy could see—”Oof!”

“Sorry,” said Alex’s mother. “This road’s not very good.”

Alex sighed. Who could write while his insides were being turned into a milkshake? The coroner looked white—even a little bit green—as he turned away from the autopsy table. “I’ve never seen anything like it!” he said. “His insides are nothing but mush—”

Not bad, Alex thought. He glanced back at his French horn case, which had started out upright and was now upside down and wedged between the back and front seats. He knew just how it felt.

The road crossed a narrow wooden bridge marked with a faded “Watch for Flash Floods” sign, turned sharply right for a few hundred feet, and then turned right again, plunging into a hollow between two hills. The late afternoon sun stretched the car’s shadow out in front of it like a bony finger pointing the way to a dilapidated house that might once have been white, an even more dilapidated barn barely a ghost of its original red, and so many cars Alex at first thought they were approaching a junkyard—except these cars weren’t junk. “You can get that many people out to an antique auction in the middle of nowhere?” he said in astonishment.

“This is a very special auction,” his mother replied as they jolted and jounced the last eighth of a mile. “Miss Elizabeth Wainscott lived here all her life—kind of a recluse. The place isn’t much, but she packed house and barn to the rafters with one of the best antique collections in Arkansas. When she died last month, her will specified that everything be sold at auction and the money given to her only surviving relative, a nephew up in Springfield. I expect—,” they swerved in behind a silver Mercedes and jerked to a stop, “—that he’ll do all right.” She turned off the engine and picked up her purse from the floor at Alex’s feet. Alex didn’t budge. His mother sighed. “You can stay here if you like, but it’s going to be a while. You might as well get out and look around.”

“Who cares about a lot of old junk?”

“Suit yourself.” His mother tossed him the car keys. “I guess you can listen to the radio.” She got out and hurried toward the house, a snatch of auctioneer’s patter rattling around inside the car as her door opened and closed.

“If you’d buy me a smartphone I wouldn’t have to,” Alex said, but not until after she couldn’t hear him. He turned the key to ACC, but all he got on the radio was static. “Stupid hills,” he muttered. He twisted the knobs a few seconds longer, then gave in to the inevitable, switched off the radio, pulled out the key and got out of the car, shivering a little at the unexpected chill in the air in the shaded hollow. Even poking around in some old lady’s knickknacks was better than slowly going crazy from boredom in his parents’ Lincoln. “The hearse stopped abruptly, and the engine died,” he muttered under his breath as he walked past the Mercedes, two BMWs and a Corvette, toward the rhythmic chant of the auctioneer. “The boy took his chance and fled, following a weed-choked path past the rusting hulks of—of—aw, to heck with it.” He kicked a Coke can out of his path and finally stopped on the edge of the well-dressed crowd surrounding the auctioneer, who stood in the bed of a pickup truck. He wore a blue western-cut suit, a red plaid shirt, a string tie and a white cowboy hat, and brandished a cane as he accepted bids on a piece of furniture that looked like a cross between a refrigerator and a chest of drawers. “Sold! A mahogany wardrobe, to the lady in red, for $2,000.” Alex gave the piece of furniture a second, more interested glance: he’d wondered exactly what a wardrobe was ever since he’d read C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. Two thousand dollars seemed to him like a lot of money to pay for a portable closet, but adults were always spending their money on dumb things…speaking of which, where was his mother?

Ah. He spotted her on the other side of the truck, looking at a table covered with odds and ends, and guessed she wasn’t ready to spend $2,000 on a mahogany wardrobe either. He edged around the crowd as something new went on the block: a collection of framed photographs, showing Wainscott menfolk in Civil War uniforms, both Union and Confederate. The auctioneer held up a photo of a boy with a bugle as a sample, and the bidding started at $100 for the lot.

“See anything you like, Mom?” Alex asked as he came up to her.

She smiled at him. “Got bored, huh?” He didn’t answer. “I’m afraid not. I was hoping for some nice old china, but Miss Wainscott seems to have been terribly hard on dishes.” She looked toward the house. “Unless there’s something on that table over there…”

She strode off but Alex stayed put, poking half-heartedly through the junk on the table. It consisted of items too small or insignificant to be auctioned individually, which instead had been dumped randomly into boxes and priced for outright sale. Alex dug through the first box, finding rusted horseshoe nails, ugly costume jewelry, a handful of stereoscopic views of Little Rock in 1905, a German Bible, three marbles, a bedraggled stuffed hummingbird posed rather stiffly on a piece of wire above a carved wooden flower, and a remarkably bad smell. The box was priced at $15. Alex snorted and wiped the dust off his hands onto his jeans. He was about to turn away when a sudden gust of cold wind blew back the flap on another box on the table, revealing the bugle.

At first sight it was ugly. At second sight it was even uglier. In fact, it was the most scratched, scarred, dented and dingy musical instrument Alex had ever seen. Parts of the tubing were so flattened he wondered if it could even be played. The chain or cord which had once kept the mouthpiece from falling off had been replaced with baling wire, and the entire horn was caked with what looked like a hundred years’ worth of dust and grease.

But ugly and filthy as it was, it drew Alex. He picked it up, and almost dropped it; it was heavier than it looked, and it felt—strange. His palms tingled and he quickly put the bugle back in the box. Grease, he told himself uneasily, wiping his hands again. The thing would need a lot of cleaning before he could blow it…

He shook his head. Was he nuts? The bugle’s box was marked at $20. Sure, he had $20, but he was saving for a telescope. He wasn’t about to spend that big a chunk of his saved-up allowance on—he glanced at what else was in the box—old clothes and a beat-up bugle. That would be crazy.

But then he looked at the bugle again, and wondered where it had come from. How old was it? Second World War? Maybe even the First? Or maybe it wasn’t that old at all, but had been damaged in a firefight in Vietnam and sent back with some dead soldier’s personal effects…did they even use bugles in Vietnam? Alex didn’t know. He ran his finger over the battered length of the instrument, and again felt that odd tingling. “What a piece of junk,” he said out loud. “Who’d pay twenty bucks for something like that?” He flipped the lid of the box shut.

But somehow, fifteen minutes later, when his mother returned to the car, he sat in the passenger seat turning the bugle over and over in his hands. His mother hardly glanced at him as she climbed in. “You were right, Alex. We should have gone home and watched Science World. Though if I’d had a couple of thousand dollars to spend on some of that beautiful old furniture—” She looked at him and stopped. “What’s that?”

Alex was used to explaining the obvious to grown-ups. “It’s a bugle.”

“I know that, but where—” She grinned suddenly. “‘Who cares about a lot of old junk?’, huh?”

“This isn’t junk. It’s a musical instrument.”

“Used to be, you mean.” His mother started the car. “Looks to me like it’s not much of anything, anymore.”

“It will be, once I shine it up. You wait and see. I’ll take it to school and blow it during football and basketball games. It’ll be great!”

“Well, I’m glad one of us got something worthwhile out of this little jaunt. As long as you don’t take to blowing ‘Reveille’ at six a.m….”

Alex laughed.

He held the bugle all the way home, stroking it almost like a cat. The tingling didn’t bother him anymore; in fact, he hardly noticed it. A new story started in his head. The antique dealer squinted at the ancient instrument through his monocle. “I don’t believe it,” he said in awe. “A Stradivarius bugle. Everyone thought he only made violins…”

Maybe it hadn’t been such a bad day after all.

***

Chapter Two: Sammy’s Offer

At home, on the old wooden desk beside his bed, the bugle seemed somehow larger and dirtier. Alex stared at it and wondered what had attracted him to it. It really was horned-toad ugly.

It won’t be once it’s cleaned up, he promised himself. He picked it up, and again was startled by its weight. He put it to his mouth to try to blow it, but when his lips touched the mouthpiece a spark cracked, and he jerked the horn down again. “Ow!”

As if on cue, someone knocked on the door. “Son?”

Guiltily—though he hadn’t been doing anything wrong—Alex tossed the bugle aside. “Come in, Dad.”

His father pushed the door open and stood in the doorway, nearly filling it. His dark blue business suit, carefully tailored though it was, always looked to Alex as though it were about to rip at the seams across his broad shoulders. “Alex, you left your French horn and that box you bought in the car. Go get them, then wash up for supper.”

“I didn’t buy any—oh!” Alex had forgotten about the box the bugle came in. More surprisingly, he’d forgotten about the French horn. The school would have his neck—and probably his allowance for the rest of his life—if he let anything happen to that horn. “There’s nothing in that box but old clothes. You could just throw it out.”

“No, you could just throw it out. Although since you paid for it, I’d think you’d at least want to see what’s inside it. Maybe there’s something under the clothes. If I were you, I’d hope so—that beat-up bugle sure isn’t worth $20.” His father, towering over him, followed him down the stairs. “I thought you were saving for a telescope. Why are you wasting your money on a piece of junk?” Alex groaned inwardly and quickened his pace through the hallway into the kitchen, where his mother was setting the table. “Maybe if you had to work for it like I did when I was growing up…”

Alex banged through the back door and out into the cool evening air. His father had a standard speech about how hard times were when he was growing up on a dry-land cotton farm in the Texas panhandle. He’d used it campaigning for town council. Trouble was, three months after being elected, he was still using it.

Sometimes Alex wished his father was still just managing a grocery store. He used to tell funny stories about the people who came in to shop. These days he always sounded more like the evening news.

In the garage, Alex pulled open the back door of the car and lifted out the French horn case. The box the bugle had come in he unceremoniously upended on the greasy shelf that ran along the wall next to his father’s silver sport coupe. The old clothes spilled out, thick with dust and as ratty-looking as though on the verge of becoming dust themselves. Years of filth hid their color. Alex poked at them gingerly. On top of the heap lay a coat, ripped across the front and stained with something darker than the dirt. Alex fingered the long, jagged tear. “Blood, inspector,” said the great detective. “The coat is stained with blood. Obviously someone—or some thing—slashed the poor man’s stomach open. No doubt he died instantly…” Alex jerked his finger back. It did look an awful lot like blood…

Well, whatever it was, he didn’t want it. He bundled the clothes back into the box and shoved it into a dark corner of the shelf. He’d throw it away later, when his father wasn’t around to lecture him about wasting his money.

He half-expected his father to ask him about the box’s contents during supper, but instead his dad went on and on—and on—about who had said what to whom at city hall that day and what whom had thought of it. Alex tuned him out and concentrated on shoveling in his spaghetti. He wanted to get back to his bugle.

Dessert over, he waited for a break in his father’s monologue, asked, “May I be excused?” and dashed up the stairs the moment his mother nodded. His father didn’t seem to notice.

When he picked up the bugle it shed flakes of greasy, reddish dirt onto his orange bedspread. He hurriedly brushed them off. The smudge blended into the color well enough he didn’t think his mother would notice.

Gingerly he lifted the bugle to his lips again. There was no static spark this time, but he didn’t try to blow it—not yet. He’d shine it up like new, and then surprise everyone with “Charge” or “Reveille” or “Taps.”

He cast around his room for something to polish with, and, finding nothing, slipped down the hall to the bathroom and grabbed one of the old washrags that nobody used anymore. Then he hurried downstairs to the dining room and liberated a bottle of metal polish from one of the many glass-doored cabinets filled with his mother’s growing collection of antique doodads. Ever since his father had been elected to council, his mother had been buying more and more of the things. The house was beginning to look like an antique shop. Useless old junk, Alex thought as he closed the cabinet door. At least the bugle is good for something. The kids in the band will think it’s great. And at the football game next Friday…

Back in his room, he sat on his bed, soaked the rag in the polish, then began scrubbing the bell of the dirty old horn. It was surprisingly hard work, but as the first small circle of pale-gold metal took shape under his rag and began to grow, Alex forgot about everything else. As age-old dirt melted away, fine filigrees of silver and gold appeared, he mentally wrote. What had been a shapeless mass of corrosion became a glittering, priceless work of art…

Two hours later he set aside rag and almost-empty bottle of polish and stretched his arms, wincing as his muscles complained. The bugle, unfortunately, did not look like a glittering, priceless work of art, or even new or almost-new—it was too battered and scratched. On the other hand, it was no longer a “shapeless mass of corrosion,” either. Instead…It looked somehow proud, like a leathery-faced ancient sailor, wrinkled and burned by the sun, every adventure of his long life etched on his face. Alex grinned and promised himself he’d remember that phrase for his next English composition. Miss Hildebrandt would like it. She kept telling him not to waste his time on horror stories, anyway.

“Now for the inside,” Alex said out loud. He took the bugle into the bathroom and put the mouthpiece end under the bathtub tap, then turned on the hot water, expecting mud, old paper, and possibly far more disgusting things to come out the other end. Instead, the water, tinged with brown but otherwise clear, spurted out of the bell almost at once. Within a few seconds it flowed perfectly clean.

Alex turned off the water and shook the bugle vigorously. It still felt heavy, but he guessed he could forget the mud-dauber theory. Maybe it was made out of a heavier metal than he was used to, that was all. He put it to his lips—

—and his mother appeared at the door. “Don’t you dare,” she said. “Your father is busy in his office and you know what he’ll say if you start blowing a bugle at this time of night. And look at the mess you’ve made! Clean out that bathtub and then throw out that filthy rag you left lying on the floor in your room. And hadn’t you better think about bed? Don’t forget we’re going to Great-Aunt Betty’s tomorrow.”

Alex groaned. He had forgotten, or his Friday would have been even more miserable. He heaved an exaggerated sigh but did as he was told.

That night he put the bugle on the table beside his bed, right where a beam of moonlight shone through a crack in the curtains. The newly polished metal glowed in the soft light as though illuminated from within. Alex blinked at it sleepily for several minutes before finally dozing off.

In the middle of the night he woke and jerked upright, heart pounding, staring around the room. The moon had set and the only light was a faint glow from the green digital display on his alarm clock. “Who’s there?” Alex whispered, certain, in that first moment of waking, that someone had been standing by his bed, and had been filling his head with confused, fiery images and sounds of thunder, but as his pulse slowed and his brain registered the familiar shapes of his chair and desk, night table and closet, and the oval shadow of the bugle, he decided he had dreamed it, and he lay back down. His right arm still ached from polishing the bugle; he rubbed it for a few minutes before falling asleep again.

The trip to Great-Aunt Betty’s got off to a bad start when Alex went out to the car with his duffel bag in one hand and the bugle in the other. His father looked up from loading the trunk and frowned at him. “No,” he said.

Alex blinked. “No what?”

“You’re not taking that thing.”

“Huh?”

“You heard me.”

“Why not?”

“We’re not putting up with the noise, that’s why. I don’t need it, your mother doesn’t need it, and I know Aunt Betty doesn’t need it.”

“But, Dad, I want to take it to school Monday and I need to practice—”

“I said no. Now take it back upstairs and leave it.”

“Dad—”

“Don’t argue, just do it!”

Alex clenched his jaw so hard it hurt, spun around, stomped up onto the porch, crashed through the back door and did his best to put his foot through every one of the stairs as he pounded up to his room. He set the bugle gently on his desk, then picked up his pillow and threw it against the wall as hard as he could before taking a deep breath and going downstairs again. He didn’t look at his father as he climbed into the car.

The weekend crawled by. As Alex knew from previous dull experience, there was absolutely nothing to do at Great-Aunt Betty’s. She didn’t even have a television—and of course, thanks to his father, Alex didn’t even have his bugle. He read three books, started four of his own in his head, and was almost glad to be going back to school the next day when they returned home Sunday evening. Monday couldn’t be as bad as Friday had been, after all; and he was looking forward to showing the bugle to a couple of his teachers.

Monday morning Alex stumbled down to breakfast in his bathrobe, rubbing sleep from his eyes, to discover his mother on her way out. She pecked him on the cheek and said, “You’ll have to fix your own breakfast, sweetie. Your father’s already gone to city hall and I’m driving out to a farm auction thirty or so miles south. There’s a silver teapot I’m dying to get my hands on…”

“But who’ll take me to school?”

“It’s nice out, you can walk. Oh, and your dad and I will both be home late tonight, too, so you’ll have to walk home or catch a ride with someone else. Fix yourself a sandwich for supper. ‘Bye!”

“But if I have to walk to school—”

The door banged shut.

“—I don’t have time for breakfast,” Alex informed the empty house, then added a word he wouldn’t have dared to use if the house hadn’t been empty.

Grabbing an apple out of the refrigerator as a poor substitute for the biscuits and gravy he’d been hoping for, he hurried upstairs to dress. He bundled his books into his knapsack and slid it on, then grabbed the bugle, carrying it in one hand rather than in the knapsack because he didn’t want it banged up any more than it already was. His French horn he left in his room; band didn’t meet today.

Out the door, down the walk, turn left, three and a half blocks to busy Maxwell Street, right on Maxwell, six blocks to the town square, another three blocks to Armstrong, turn left two blocks, and there was Edmund Kirby-Smith Junior High School in all its glory, its red brick shining in the early morning sunshine, the grass around it still green though October was all but over, the oaks and maples surrounding it with red and gold. It looked like paradise.

Alex paused across the street and took a deep breath. There could be no better example of looks being deceiving than the peaceful appearance of Edmund Kirby-Smith Junior High School. He took a firmer grip on the bugle, resisting the impulse to blow “Charge,” and strode across the street and onto what he increasingly thought of as a battlefield.

He wondered sometimes why he didn’t write a real horror story: “I Was a Junior High School Student.” Rated R: some scenes too frightening for those under 16. Including those with the lead roles.

Actually, it’s more of a minefield than a battlefield, Alex amended as he hurried down the long concrete walk to the gray-columned porch of Kirby-Smith’s main entrance. Or maybe a barnyard: you just have to watch where you step. Stay away from certain people, walk quietly, and if you’re lucky, nothing will blow up in your—

“Hey, Mitchell.”

A boy stepped in front of Alex; a boy built a lot like Alex’s father. Alex recognized him, and his heart started to pound like it had Friday night when he’d awoken from that strange dream.

He didn’t bother talking to the monster in front of him; it was Billy Jones, the only six-foot, two-hundred-pound fourteen-year-old Alex had ever seen. There was no point in talking to Billy, because Billy never had anything to say for himself. The only time he talked, or did anything else for that matter, was when he was told to by—

Alex turned around. “Hello, Sammy.”

Sammy Findlater stood behind him with three other boys: the twins, Simon and Arthur McKissick, dark-haired, dark-eyed, always with Sammy, as though he cast a double shadow; and Norman “Razorback” Aiken, blonde, freckled, with blue eyes, a charming grin, and a reputation for being the second-meanest kid in school—Sammy, of course, ranking first.

“Got a new toy, Mitchell?” said Sammy.

“What?” Alex followed Sammy’s gaze to the bugle. “Oh, that. It’s just an old horn I bought at an auction sale yesterday, Sammy—paid too much for it, too.” He laughed. It sounded like a squeak—even to him.

“Sorry to hear that,” said Sammy solicitously. “Tell you what, then. I’ll do you a favor and take it off your hands.”

Alex swallowed, very aware of Billy looming over him—in fact, of everyone looming over him, because even Razorback and the twins, who were only of average height and build, had several inches and pounds on him. “Look, Sammy, I’m sorry about knocking over your model—”

Sammy took a step closer. “Hey, no problem, Mitchell. That’s why I’m offering to take that piece of junk—just to show there are no hard feelings. Besides, I kind of like its looks.”

Alex tried to back up, and bumped into Billy’s stomach. “Really, Sammy, you don’t have to—”

“Oh, I know I don’t have to, Mitchell, but I want to. I want to do this for you. Look, it’s worthless, right? It’s so beat up I’ll bet the scrap yard would charge you five bucks just for the trouble of throwing it away. But I’ll take it for free.”

Stalling, as much as anything, Alex asked, “Why?”

“You know me, Alex, I just take a fancy to things sometimes.”

Oh, yes, Alex knew Sammy—until now only by reputation, but reputation was more than enough. He’d heard all the stories, the ones that circulated among the kids but the grown-ups either never heard or discounted. Russ McKinley had brought his brand-new bike to school. Sammy had taken a “fancy” to that, too. Russ wouldn’t let him ride it, and when he came out after school all the spokes had been kicked in, the tires and seat had been slashed and even the frame was bent. Another boy had been showing off an expensive new shirt; Sammy had wanted to “borrow” it. Of course it was just an accident, but Razorback was running through the schoolyard that afternoon and ran right into the kid who owned the shirt, and somehow it had gotten ripped…

And now Sammy wanted the bugle.

I should just give it to him, Alex thought. It’s not worth anything, not really. It’s just an old piece of junk.

But he’d worked his arm to a nub polishing it, and it had cost him $20 of his hard-saved telescope money, and he hadn’t even had a chance to blow it yet, and anyway, just who did Sammy Findlater thank he was, Al Capone? Alex face and ears felt hot and his heart beat faster than ever. He opened his mouth to say “no,” but somehow two other words came out instead, two words that, on top of what he had said in the house that morning, would have gotten him grounded for a week if his parents had heard him.

As it was, they got him grounded immediately. Sammy stiffened and nodded once at Billy. Something slammed into Alex’s back and he crashed to the ground, twisting at the last second to keep from falling on the bugle, and bruising his shoulder instead. “Take it,” he heard Sammy say, and instinctively he grabbed the bugle with both hands and curled himself around it as someone kicked him in the leg and someone else kicked him in the back and big hands pried inexorably at his arms and all around kids were shouting and screaming—

Then suddenly Sammy yelled, “All right, break it up, break it up,” and hauled Alex to his feet, brushing the dirt off him and asking anxiously, “Are you all right?”

Alex wasn’t at all surprised to hear the vice-principal say from behind him, “What’s going on here? Alex?”

Alex met Sammy’s eyes. “Nothing.”

“It didn’t look or sound like nothing. Sammy?”

“I think it was just a little game that got out of hand, sir,” Sammy said in his best apple-pie voice.

The vice-principal looked from Alex to Sammy to Billy to Razorback to the twins. “All right, we’ll let it go,” he said finally. “But y’all know the rules about fighting.”

“Yes, sir,” they said in unison—except for Billy, who said nothing.

“Good.” The first bell rang. “Don’t let it happen again. Get to class.”

Alex started toward the door, but a hand on his sore shoulder stopped him. He looked around at Sammy, who smiled sweetly and said, “Later,” then brushed past him and led his four followers into the school.

Alex, still clutching the bugle tight against his chest, limped after them.

***