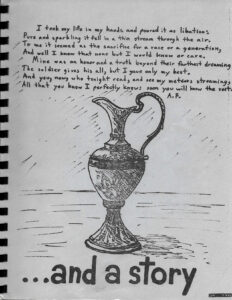

Way back when I was in my last semester at Harding University in Searcy, Arkansas, in the fall of 1979, a friend of mine, Rick Hamill, spearheaded a literary magazine which ended up being called …and a story, the name deriving from the fact it was all poetry except for one short story–mine.

I’ve had that little magazine ever since, and finally dared to re-read the story. It’s really not bad, coming from 20-year-old me, and actually, given the current of cancel culture swirling around us right now, almost seems a little too current.

Here it is. Enjoy! (By the way, I also drew the cover art.)

The Price of Love

By Edward Willett

Liola tossed and turned in her bed, the day’s events having left her too troubled to sleep. Who would have thought that one day could turn her world upside down like this?

It had started normally enough. She was silently awakened by her bed at the usual time, had used the ’fresher, eaten breakfast with her father (her mother, by that time, was already at the chemical research lab where she worked) and grabbed the tube to the EdComplex, it being a Meet day. Usually, the students were scattered all over the city, training in their various fields or doing their Generals on their home terminals. But on Meet days, the entire student body went to the Complex for Ethics training, physical education, and what was referred to as “necessary social contact with one’s peer-group.”

For Liola. that meant Alisha, her best friend. They had met at the first Meet that year, discovered they lived in adjacent buildings, and were soon very close.

Used to be close, Liola thought, and buried her face in her pillow. Did I do the best thing?

It was right after Ethics that it happened. As usual, they had done a role-play, this one a classic survival play in which the ten students in their group were assigned the roles of people wrecked on a desert island that could not support all of them. They had to decide which ones were most suited to survive. Alisha had been very quiet, not fulfilling her role requirements at all, and from the way the Ethics teacher had been frowning, Liola knew her friend was in trouble.

After the class, on the way to PhysEd, Liola said, “What’s wrong with you, Lish? You know you have to get a good grade in Ethics. If you keep on the way you’re going, the EdBoard won’t give you a job recommendation!”

Alisha sighed. She was a tall, brown-haired and brown-eyed girl. She was the same age as Liola, fourteen, but Liola often thought Alisha seemed much older. This was one of those times.

Alisha stopped and looked around them. They were in the Greencourt, where carefully tended trees and flowers grew in the quadrangle formed by the buildings of the Complex. There was no one near. “I can’t say what I don’t believe,” she said, “and I’d have to, to pass Ethics.”

Liola didn’t understand. “What do you mean, what you don’t believe? Of course, you believe in Ortho Ethics. Everyone does! I suppose you’re not Ortho!” She was joking, of course. Everyone was Ortho—Orthodox Humanist, the world system of belief that had replaced religions and abolished war.

Alisha smiled sadly and traced something on the ground with her foot. Liola followed the invisible lines but could make no sense of the fish-like shape they pictured. She looked up at Alisha, puzzled. Alisha turned very serious. “Liola—can you keep a secret?”

“Of course I can,” Liola said eagerly.

‘‘I’ve known you for a long time,” Alisha said. “I think I can trust you—and I need to tell someone.” She paused.

“Well?” Liola said breathlessly.

“Liola, I—I’m not Ortho. And neither is my family.”

‘‘You mean you’re—you’re Nihilists?’’ Liola was aghast. Her best friend, one of those who denied the basic Ortho tenet that you can do anything—as long as it hurts no one else? The Nihilists just stopped with, “You can do anything.”

“No!” Alisha denied vehemently. “We’re Christians!”

The word seemed to hang in the still air, and Alisha glanced hurriedly around. They were still alone. Liola’s expression didn’t change. “But—but that’s even worse!” she blurted. “Christians are pleasure deniers, and proselytizers—and spiritualists, subversives—”

Alisha was turning pale. “I thought I could trust you!” she whispered. “But you’re just as brainwashed as everyone else!” She turned and ran from the EdComplex, dropping her carryall.

Dazed, Liola picked up the bag and also left the Complex. For a long time, she walked aimlessly. All her life, she had been told how the Ortho doctrine had given Man the stars, endless food, bountiful energy; how the outlawing of religion had ended the petty bickering of men over silly superstitions and freed the human mind for greater and greater advancement; how anyone who denied the Orthodox Humanist doctrine was antisocial and had to be removed from society before their poison corrupted others. She knew what she should do, but Alisha and her family were her friends!

It was dusk before she went to the Admintower and registered at the appointment terminal. ‘‘Liola Terris, UX/00955/FG,” she typed into it. “I have information on a group of Christians meeting within the city. Please contact me for data.” A glance at the status board showed her that the Admintower was closed for that day, but information of the type she offered was urgent. She would get a call as soon as the building opened the next day.

Now she was in bed, it was after midnight, but still, she could not sleep. Not after what she had done. I did the Ortho thing, she told herself firmly. I helped society. Society is more important than a selfish friendship.

But she trusted you. Alisha—your friend—trusted you.

Society comes first! she repeated to herself.

. . . your friend . . .

In the end, she got up and flipped on her desk light. She opened Alisha’s carryall, hoping to find something that would relieve her guilt. A letter with something nasty written about her . . . some evidence that Christians were as bad as she had been told . . .

Aside from the usual items, all she found was a thin book, The Development of Orthodox Humanism. A terrible suspicion flooded her. What if Alisha had been joking? She opened the book.

Her first feeling was one of relief—it was a Christian book. Her report to the Admintower had been truthful. She glanced at the book with the sense of looking at something forbidden. There were many passages underlined, and the type was interspersed with numbers. With sudden resolve, she turned back to the beginning and began to read. She was condemning her friend to exile; she wanted to know for what.

She was still awake several hours later when her terminal chimed for her attention. For an hour, she had been sitting in silence, trying to digest the things she had read. Alisha believes all of it, she thought. All of it . . . phrases floated through her mind. Forgive them, they know not what they do . . . Love your neighbor as yourself . . . and she knew, beyond a doubt, that Alisha would forgive her. That should have made it easier to answer the chime of the terminal, but it didn’t. It somehow made it harder to know that even after this, Alisha would still love her.

A grim man in the uniform of the Peacemen appeared on her screen. “Liola Terris?” the man snapped.

“Yes, sir,” Liola said.

“Speak up, girl!”

Liola cleared her throat. “Yes, sir,” she said a little louder.

“I have your appointment note here. You know of a group of Christians?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ah!” The officer leaned forward eagerly. “You will be rewarded. Who are they, and where do they meet?”

Liola was never sure where the next words she spoke came from. It was as if all her thinking and reading of the night came together, and while a part of her listened in horror, the greater part of her rejoiced as she said, “I won’t tell you, sir.”

#

Three days later, she stood in the dock of the Ortho Court while the red-robed judge pronounced sentence. Throughout the trial, she had told the truth: yes, she knew a group of Christians, and no, she wouldn’t tell them anything.

‘‘Whereas Liola Terris, Society Number UX/00955/FG, has confessed that she is willfully withholding the knowledge of the whereabouts of an anti-Ortho group known as Christians, she is pronounced guilty of the crime of subverting society and is hereby sentenced to the full penalty of the law: exile, by next available starship, to an alien planet from which she may never return to Earth.” His gavel banged. “Court adjourned.”

Liola’s parents had sat stiffly and silently throughout the trial, after their initial horror and dismay that their daughter could do the terrible thing ascribed to her. Now they turned away from her, and without looking back, they left the courtroom. Liola knew she would never see or hear from them again. As far as everyone on Earth was concerned, she no longer existed.

Not even for Alisha, Liola thought bitterly as she was led back to her comfortable, if drab, detention cell. I saved her, but she didn’t even come to the trial. Not that she could be blamed, Liola admitted; it would have been dangerous for all the Christians if she had. Liola had disposed of Alisha’s carryall before the Peacemen had arrived, but Alisha could not have known that; she must have been fearing arrest since its loss.

Still, as the cold realization of what would happen to her sank in, the feeling of rightness, of having done what she should have done, began to desert her. How could she have tossed off fourteen years of training in Ortho Ethics just like that—on the basis of a book of ancient myths?

The question tormented her for the two days she had to wait for “available transport.” She knew she could still tell them what she knew and earn pardon, and the temptation grew. Her self-respect held her back. But to save herself from exile . . .

The temptation was still there when, two days after the trial, she was taken by Peacemen to the spaceport to be assigned to an exile world. There were several of these. The Orthos were humane: each type of subversive was sent into exile with others of his or her kind. But the worlds were primitive, and once on them, there was no escape.

Liola was not surprised to be assigned to the Christian world, a newly opened planet of exile with only a few hundred inhabitants, for Christians were not reported often. Her resolve at a low ebb, she followed the Peacemen toward the shuttle that would take her to the orbiting starship.

Then she saw a tall, brown-haired girl of her own age appear on the loading ramp. “Alisha?” Liola cried. Her doubts vanished as she ran up the ramp. The two hugged each other tightly, then Liola stepped back. “But I didn’t betray you, Alisha. Why—?”

Alisha smiled through tears. ‘We heard what had happened to you, how you said you knew of a group of Christians, then refused to betray them . . . how you were sentenced to exile for it, and your parents deserted you. We talked about it a long time, and finally—we turned ourselves in. My parents are already on board the shuttle.”

“But why?” Liola said.

“For you,” Alisha said simply. “For what you did for us. You lost your planet and your family. We can’t give you back Earth—but we’ll be your family.” She smiled again. “And, if you wish, you can be part of our greater family—all our thousands of brothers and sisters in hiding.”

Liola felt warmth creeping into her frozen soul. Thousands of brothers and sisters—all united in a way no other family was united. She found herself smiling back, though tears dimmed her eyes. “I’d like that,’’ she said.

“I’ll teach you,” Alisha said. She hugged Liola again. “We’d better get inside,” she said, and together Liola and her new sister walked up the ramp into exile—in a universe of love.