Amazon U.S. | Amazon Canada | Indigo | Barnes & Noble | Penguin Random House

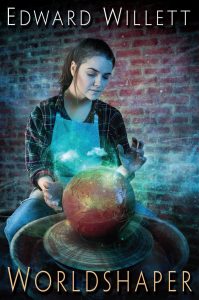

My ninth novel for DAW Books, now out in trade paperback and ebook (a mass-market paperback will appear at a later date) starts a new series called Worldshapers. The artwork is by Juliana Kolesova.

“This rollicking secondary-world contemporary fantasy opens with a bang…(the characters) grapple with the ethics of changing the world, the question of what makes people ‘real’ when the worldshapers can change everything about them with nothing more than a thought, and the need to save the universe. Willett…meticulously includes small details that make the constantly changing scenery feel solid and real…This novel sets up a fascinating, fluctuating universe with plenty of room for growth for the main characters, and readers will eagerly join their journey.” – Publishers Weekly

“Willett’s series starter is fun, quirky, and highly enjoyable, nicely laying the groundwork for future volumes.” – Booklist

“There is so much to love about this book. Like the fact it references Tolkien at least three times, if not more. Or perhaps the fact it referenced Doctor Who. Or maybe the fact that it’s got a sarcastic wiseass smartmouthed main female character who actually stops to think ‘what-if’ every once and a while. Or perhaps there’s the fact that there are so many interesting ideas in this book that it’ll make your world spin….Edward Willett is fast becoming my favorite author.” – Ria P., NetGalley reviewer

Description:

From an Aurora Award-winning author comes the first book in a new portal fantasy series in which one woman’s powers open the way to a labyrinth of new dimensions.

For Shawna Keys, the world is almost perfect. She’s just opened a pottery studio in a beautiful city. She’s in love with a wonderful man. She has good friends.

But one shattering moment of violence changes everything. Mysterious attackers kill her best friend. They’re about to kill Shawna. She can’t believe it’s happening–and just like that, it isn’t. It hasn’t. No one else remembers the attack, or her friend. To everyone else, Shawna’s friend never existed…

Everyone, that is, except the mysterious stranger who shows up in Shawna’s shop. He claims her world has been perfect because she Shaped it to be perfect; that it is only one of uncounted Shaped worlds in a great Labyrinth; and that all those worlds are under threat from the Adversary who has now invaded hers. She cannot save her world, he says, but she might be able to save others–if she will follow him from world to world, learning their secrets and carrying them to Ygrair, the mysterious Lady at the Labyrinth’s heart.

Frightened and hounded, Shawna sets off on a desperate journey, uncertain whom she can trust, how to use her newfound power, and what awaits her in the myriad worlds beyond her own.

Chapter One

Karl stumbled through the door, spun, slammed it closed, then slapped his palms against the rusty steel. Blue light crackled across the metal, briefly outlining the KEEP OUT: DANGER sign, faded red paint on white, that hung at eye level.

He rested there for a moment, breathing hard, then straightened and turned to see what kind of world he had entered.

He stood in a dark, rough-hewn tunnel of stone, narrower at the top than at the bottom, shored up by beams of dark wood. A dim light bulb, hanging on a twisted pair of rubber-coated wires, glowed overhead, swaying from the gust of warmer air that had entered this world along with Karl. The swaying bulb cast shifting shadows up and down the walls and across the floor, but he could see well enough to make out two metal rails, spanned by rotting wooden ties, running along a rubble-strewn floor toward the faint outline of another door. The gray light seeping around its edges spoke to him of twilight, though whether morning or evening he did not yet know.

He turned to look at the door he had just closed. On this side, it was made of rusty steel and set in a barrier of corrugated metal. Bits of broken chain scattered the floor beneath it, and a shattered padlock lay near his feet. No lock or chain could hold against the opening of a Portal.

No light spilled from beneath the door, even though he had come through it from the common room of a torch-lit inn. No sound came through it, either, though the inn had been bustling. The man who had been following him, who had started running through the common room, shoving people out of his way as Karl opened the Portal, had been too slow. By the time he opened the wooden door he had seen Karl pass through, he would find nothing beyond it but the inn’s pantry.

That should have been the end of pursuit, but Karl had thought the same when he’d entered the world he’d just fled . . . and somehow the Adversary had followed him into that world, even though he had closed the last Portal behind him exactly as he had closed this one. Which meant, if the man who had been following him was a servant of the Adversary—as he almost certainly was—soon enough the Adversary would come to this Portal, and perhaps force it open as well.

Which meant his time was limited. He needed to find this world’s Shaper, see if this one might be strong enough to do what Ygrair required, and if so, convince or coerce him or her to accompany him.

He had no reason to hesitate, and indeed, every reason to hurry, but hesitate he did. He had entered many worlds, yet this one gave him pause. Without taking so much as a second step into it, he knew from the flavor of the air, from the way its gravity tugged at him, from the faint echoes of his breath and movements back from the tunnel’s stone walls, that this world was similar . . . very, very similar . . . to the First World, the one from which Ygrair had taken him . . . how long ago had it been?

An old way of thinking, that. Time flowed differently from world to world within the Labyrinth. How could you measure time when some of worlds you visited did not orbit suns, but were orbited by them, or were lit by flaming chariots drawn by fiery flying steeds, or were not lit at all, except by the moon and the glow of the eldritch stones that paved their roads and formed the walls of their strange, twisted buildings?

Each world in the Labyrinth was Shaped, to a greater or lesser degree, by a singular imagination. This one had been Shaped less than most, so that it closely resembled the First World—but it was not the First World. Just another world in the Labyrinth. Nothing special at all.

He glanced back once more at the metal door. In any event, if the Adversary were able to enter this world as he had the last, it would soon be re-Shaped . . . unless its Shaper was, at last, the one Ygrair had sent him to seek.

He turned away from the closed Portal for good, then, and strode toward the door into the outside. It opened with a push, and he stepped out into the fresh air of a mountain evening. He took a deep breath, enjoying the scent of pine, then looked up at the starry sky. The constellations were the same ones he had seen as a child, lying on his back in the yard of his father’s farm, dreaming of the day he would be old enough to leave it. The Earth’s great cities had seemed like different worlds to him then, and he had longed to see them all: New York, London, Paris, Berlin.

He’d done it, too, travelling to those and so many more. He’d even created his own worlds, after a fashion, on stage and in his words. But then Ygrair had literally fallen into his life . . . and he had learned just how stunted his understanding of new worlds had been.

And she has promised, he thought. Someday I, too, will have a world to Shape.

But only if he succeeded at the daunting task she had set him. Which I had better be about. Lowering his gaze, he strode into the darkness.

#

I could feel the coming storm in my bones.

“Can’t you guys work any faster?” I called up to the two young men standing on the scaffolding outside my two-story shop/apartment, right in front of my bedroom window. I wondered if I’d remembered to close the blinds. I hoped so, because I’d not only failed to make my bed, I was pretty sure I’d left underwear on it.

Neither one looked at me, probably because they were trying to bolt a big capital W made of brushed steel to the century-old building’s worn red bricks. “Don’t worry, lady,” called down the older of the two, although older in this case meant he’d been shaving for maybe six years, as opposed to three. “Should be done by lunch.”

“What’s it going to say?” said a voice behind me. I glanced around to see a pixie-ish college-aged girl, blonde hair piled up in an oh-so-casual-yet-terminally-cute fashion, with just the right number of stray strands falling across her forehead above her bright blue eyes. She wasn’t looking at me, though: she was looking up at the young men, although I wondered whether it was really the sign that had drawn her interest, or the unique view available from this angle of the fit young men in their tight blue jeans. (Not that I’d noticed . . . okay, I’m lying.) The girl held a tall, blue-and-white-checkered paper coffee cup, topped with a bright-red plastic lid, trademark of the Human Bean, half a block away and just around the corner.

“Worldshaper Pottery,” I said.

“Kind of long,” she said, never taking her eyes off the men. “A lot of letters!” she called up.

“Tell me about it,” shouted down the younger of the two. Pretty college girl, he looked at.

“Careful!” the other man snapped, as the W slipped a notch.

The younger man turned and lifted it again. “Sorry, Al!”

“So, you do pottery?” College Girl said to me, though without expending the effort to actually turn her head. “What sorts?”

“All sorts,” I said. “Anything in clay. Pots, plates, mugs, vases, cups, saucers. You name it. I have a card, if you’re—”

“Cool,” she said, in that absentminded tone you use when you’re responding to someone whose words just went in one ear and out the other. She sipped more coffee and kept watching the workmen.

I sighed and turned my own gaze west, up the street, toward the distant line of mountains. Their snowcapped peaks, sparkling in the sun in the crisp autumn morning air, were dwarfed by the towering piles of cloud behind them: white on top, a menacing dark blue beneath. I didn’t like the look of them one bit. They looked like any other line of storm clouds, but in some weird way, deep inside, they felt . . .wrong.

The weird thing was, over the past couple of days the forecast hadn’t said a word about a possible storm. It still didn’t. I’d checked the weather app on my HiPhone half a dozen times that morning: nothing. But then, the forecasters were based more than a hundred miles away in the state capital of Helena, and their inability to accurately predict what would happen in our little city of Eagle River was so well-known that local residents joked about planning their day’s activities based on the exact opposite of the forecast weather.

What surprised me more than the lack of storm warnings was the fact that no one but me seemed worried. I glanced at College Girl. “Those clouds over the mountains look nasty,” I said conversationally. “Don’t you think?”

She finally looked at me, then at the mountains, then at me again. She shrugged. “They’re just clouds. Anyway, a little rain would be nice.” She turned her attention back to the young men.

A little rain? I frowned at the mountains. Torrential rain with damaging wind, hail, possible tornadoes, serious lightning, and flash flooding, if I were any judge. In fact, the clouds had risen visibly higher just in the short time I’d stood there, and beneath their white heads and shoulders, their hearts were black as night. Okay, that might be bit overdramatic, I thought. I studied the clouds some more, then shook my head. No, it isn’t. I looked back up at the workmen. “Please hurry!” The guy who had grinned at College Girl finally looked at me, but all I got was a teenaged-boy-to-nagging-mother eye roll.

I was notold enough to be his mother. But if I was, I would have grounded him on the spot.

Giving up, I turned to College Girl again. “Want to come in and have a look at the shop? First day open!”

She gave me a perfunctory smile. “Nah, I’m good.” She tossed back the last of her coffee, took one more appreciative look at the workmen, then walked on down the street, throwing her cup into a blue recycling bin as she went.

“Come back any time!” I called after her. She raised her left hand and wriggled her fingers, but didn’t look around.

Not a great start to my first day in business, but it was early yet. While College Girl and I had been “talking,” a dozen other people had hurried past without stopping to look up at the sign or its installers, or (more to the point) into the shop windows. Then again, the scaffolding wasn’t doing anything to make the shop look inviting, and anyway, it wasn’t even nine o’clock. The people passing weren’t shoppers, they were on the way to work. Once the sign was up and the scaffolding gone, no doubt customers would pour into Worldshaper Pottery.

They’d better, I thought, thinking of the size of my lease. I yawned and rolled my head, trying to ease a kink in the back of my neck. I hadn’t slept well for two nights, and the reason why made me turn and survey the people strolling, striding, or—in the case of the teenager looking at her smartphone—stumbling along the cobblestones, between spindly trees, flower planters, and decorative benches.

Worldshaper Pottery had an ideal location—I’d been incredibly lucky to get it—on Blackthorne Avenue, which was pedestrian-only for four blocks. My shop was on the north side of the street at the far west end, half a block from busy 22nd Street (which the Human Bean fronted) and only a block from one of the public parking lots where people visiting the pedestrian mall left their cars while they enjoyed a stroll over the cobblestones. The “Shoppes of Blackthorne Avenue,” as the local business association styled itself (apparently there’d been a sale on pretentious silent Es) catered to the artsy foodie crowd: galleries, boutiques, restaurants, brewpubs, and coffee and tea shops. (Sorry, “shoppes.”) To paraphrase Ol’ Blue Eyes, if I couldn’t make it here, I couldn’t make it anywhere.

Normally Blackthorne Avenue was deserted in the early morning, once the last of the craft-beer drinkers had headed home. But for the last two nights, it hadn’t been.

It had started Sunday night. Brent, my tall, dark-haired, handsome, and awesomely fit boyfriend (I know, I know, he sounds like something from a romance novel, but what can I say? I lucked out) had just left, after spending the day helping me set up the workshop. Normally he might have stayed over—normally I’d have insistedhe stay over—but he’d had to work early the next morning and I was too tired to think straight, my libido as exhausted as I was.

As a result, I was alone when I clawed my way up out of sleep, only to find that I wasn’talone, that someone was standing at the foot of my bed, a tall figure, just a shadow barely visible in the darkness of my room, though I could tell it wore a long coat and a broad-brimmed hat. Beneath that hat glinted two cold sparks of light, reflections from the eyes staring down at me. I tried to scream, but could only manage a strangled moan; tried to sit up, but couldn’t move a muscle. I could only wait, helpless, for the intruder to do whatever horrible thing he intended . . .

And then he had vanished, and I was really awake. I gasped, sat up in bed, and snapped on the lamp on the side table. I touched my HiPhone and it lit to show the time: 3:10 a.m.

There was no one in the room with me. There never had been, of course—I knew that. It was just a dream. No, sleep paralysis, that’s what it was called, where you think you’re awake but you can’t move and you hallucinate someone standing by your bed—or in some cases, a monster sitting on your chest. I’d read up on it once because I’d experienced it before—not often, but often enough to recognize it.

But this one had seemed, somehow, more real than the other incidents I remembered, and so even though I knew it was silly, I got up, pulled on my warm, brown terry cloth bathrobe, and checked the apartment. No one there but me, of course, and the door was locked.

A cool breeze through the open window lifted the curtains. Though I was on the second story, and the window was much too high above the sidewalk for anyone to have climbed through it without a ladder, I decided I’d feel better if it were closed and locked for the rest of the night.

As I reached out to pull it shut, I saw someone standing in the middle of the cobblestoned street, in a shadowed spot ill-lit by the old-timey wrought-iron streetlamps: a tall man, wearing a long black duster and a cowboy hat. While neither of those were unusual apparel in our western town, the sight stopped me cold, hands frozen on the window frame, because I suddenly realized the figure in my dream had been wearing the same thing.

The man’s head was tilted back. I couldn’t see his eyes in the shadows beneath the brim of his hat, but knew without a doubt he was staring straight at me. It didn’t feel like his gaze had just been attracted by my silhouette against the bedroom light: it felt like—in fact, I was certain—he had been standing there, staring at my window, a long time.

I slammed the window shut, latched it, and scrambled back into my bed, without taking off my robe or turning off the light. I felt like a frightened little girl, and I didn’t like it. Questions darted through my mind: Who is he? What’s he doing out there? And, scariest of all, How did he get into my dream?

I didn’t believe in ghosts. I didn’t believe in ESP. I didn’t believe in omens. But I knew what I’d seen, in my night terror and out my window.

I lay there, hardly breathing, every sense straining, listening—sometimes imagining—a sound from downstairs. Finally, I couldn’t stand it any longer. I got out of bed, turned off the light, crept to the window, split the curtain no more than an inch with my hand, and peered out into the street once more.

The streetlights showed nothing but cobblestones, benches, trees, and planters.

I opened the window and pushed my head out through the curtain so I could look both ways along the street. Nothing moved, except for a cab on 22nd Street, which passed the end of Blackthorne Avenue without slowing.

I closed the window again, let the curtain fall shut, and climbed back into bed. I checked the clock. 4:02 a.m. I lay there staring at it, certain I’d be up until daylight . . . but as my adrenaline drained, exhaustion from the day’s work flooded back in, and I soon slipped back into sleep.

I woke later than I should have, with another day of preparing the shop for Tuesday’s opening ahead of me, this time without Brent’s help. I also woke feeling singularly unrested, the night’s unease clinging to me all the next day like stale cigarette smoke.

That night, Brent took me out to dinner, but since he was still on an early-morning work schedule and I was even more exhausted then the previous night, he left my place about ten. I didn’t tell him about my dream, or the man in the street. After all, by morning I hadn’t been entirely sure I’d really seenthe man in the street. Maybe I hadn’t been as awake as I thought, and he’d been nothing but a slow-to-fade fragment of my nightmare. By the end of the work day I’d pretty much decided I’d imagined the whole thing, and there was no point worrying Brent about a bad dream.

But that night I woke from anotherbad dream, this time one of those dreams that deeply unsettles you, but you can’t remember a single detail of the moment you’re awake. The clock radio informed me it was 4:09 a.m. I went to the bathroom. As I returned to bed, I decided—I don’t know why—to take another peek out the bedroom window, still closed and latched from the previous night.

The workmen had already erected the scaffolding by then, but it didn’t block my view of the man in the duster and cowboy hat, standing in exactly the same dim-lit spot as the night before, once more looking up at my window. With my bedroom light off, I could even see the glint of his eyes in his shadowed face. My hand tightened on the curtain and my heart pounded in my chest.

He couldn’t possibly have seen me. But he certainly gave me the impression he could. When he turned and walked away, I scurried back to bed, and this time I didlay awake until daylight, listening for the sound of someone at the door.

Chapter Two

Two days after Karl Yatsar had passed through it, the rusty red door in the abandoned mine tunnel burst open again, with a flash of blue light and a sound like a thunderclap. Like the chain it had replaced, the new chain locking the door shattered, shiny silvery links skittering across the floor and ringing against the metal rails. The single incandescent bulb lighting the tunnel swayed, sending black shadows dancing.

From the flickering torch-lit dimness of the room beyond the door stepped an ordinary-looking young man, of medium height and medium build, his hair and eyes both the same shade of mahogany brown. Like Karl before him, the young man stood in the tunnel and looked around at the rough-hewn stone walls and ceiling, at the twin metal rails stretching to the dim outline of the door at the tunnel’s exit. Unlike Karl, he did not turn and close the door through which he had come.

Twelve more people came through the door behind him, eight men and four women. They wore unmarked black military-style uniforms. They carried automatic rifles, along with pistols and knives. The young man did not turn to look at them. Instead he strode toward the tunnel’s exit. The armed cadre followed.

Beyond the stone walls, thunder grumbled. A flash of lightning limned the outline of the door at the far end of the tunnel.

The young man strode to that door and pushed it open.

He had another world to conquer.

#

The workmen arrived far too early the next morning. While they began unloading the letters from their truck, having been given special permission to drive into the pedestrian mall for the purpose, I called my friend Policeman Phil—technically Sergeant Phil Jensen, but we were both from the same small town in Oregon, and I’d known him since junior high. “I think I have a stalker,” I said into the phone.

The response was . . . underwhelming: a long silence that somehow also managed to convey disbelief, followed by a sigh. “Is this a joke, Shawna?”

“No!” I said, offended. “Would I joke about something like this?”

“Honestly? Yes. Remember that time in high school when you—”

I cut him off. “Okay, okay. No need to bring up ancient history. But I’m not joking this time. This is an official call to an official police sergeant.”

I paused. Silence.

“That would be you,” I prompted.

Another sigh. “All right, I’ll bite. Why do you think you have a stalker?”

“Because at four o’clock this morning I looked out my bedroom window and saw someone staring up at my apartment,” I said. “The same man who was also staring up at my apartment the night before.”

The pause this time was shorter. I sensed frowning. You might not think that’s possible over the phone, but with someone you’ve known as long as I’ve known Policeman Phil, it totally is. “And what did this person look like?”

“Tall. Thin. Wearing a duster and a cowboy hat.”

“A duster and a cowboy hat.”

“Yes.”

“Like how many other guys in Eagle River?”

“It’s not my fault my stalker is a walking Western cliché.”

Another sigh. “And was he there at the same time the night before?”

“Not quite. The first night it was 3:20 a.m.”

“And what made you look out of the window at 3:20 a.m.?” Phil said, a reasonable question I’d rather hoped he wouldn’t ask. “Did you hear something?”

“No,” I said, reluctantly. “I’d had a bad dream.”

“What kind of dream?”

Drat. “I dreamed someone was standing at the foot of my bed.”

“Someone? What did this someone look like?”

Double drat. “Tall. Wearing a long coat, and . . . ”

“And a cowboy hat.”

“Well . . . maybe.”

Phil said, with studied neutrality, “Don’t you think it’s possible that you simply saw someone passing in the street and projected the bad dream you’d just awakened from onto him?”

“Why was anyone out there at 3:20 a.m.?” I countered.

“There’s nothing illegal about being a night owl.”

“Two nights in a row? Staring up at my room?”

“Maybe he’s a bartender heading home after his shift.”

“That doesn’t explain him staring up at my room.”

“Maybe he wasn’t. He might have been looking at the stars. Or a bird. Or a plane. Or a satellite.”

“Two nights in a row?” I said again, with more heat.

Another pause. Then another sigh. “All right, Shawna. Tell you what: I’ll make sure someone keeps an eye on your end of Blackthorne Avenue for a couple of hours tomorrow morning. If we see someone who matches your description, we’ll have a chat with him. Best I can do.”

I felt a surge of relief. “Thanks, Phil.”

“You’re welcome. Have a great day, Shawna.”

He’d hung up. I’d put down my phone and rubbed my forehead. Then I’d tried to call Brent, but I couldn’t get an answer. That wasn’t a big surprise. The plumbing company he worked for was involved in the construction of the big—well, big by Eagle River standards, anyway, fifteen whole stories!—office tower downtown, and he was putting in twelve-hour days.

Shortly after I’d talked to Policeman Phil, the workmen had arrived, I’d officially opened the shop for the first time (although the grand opening would take place in three weeks, in early November, to cash in on the pre-Christmas rush, and would include a ribbon-cutting by Mayor Fougere, for whom I’d once made a set of plates). Now I needed to do some actual clay-shaping, and standing there watching the boys installing my sign wasn’t going to a) make them move any faster or b) accomplish anything else. I took another look at the gathering storm clouds, trying to ease my unease at their steady approach (with no notable success), then ducked under the scaffolding and went inside.

The shop wasn’t quite decorated the way I wanted it—I still had some paintings in storage I hadn’t wanted to hang while there was a chance they might be damaged, and there were two light fixtures still on order—but it didn’t look bad: bright and cheery, with glass shelves artfully (I hoped) displaying a selection of my wares. An arch behind the counter gave a clear view of the workshop: people like getting a glimpse of the potter at the wheel. Lots of people like potters. Especially hairy ones. (Sorry. Although if I were more hirsute, I would totally have named my shop The Hairy Potter.)

The work I needed to get to was an order for two dozen coffee mugs for Carter Truman, manager of the Human Bean, of a design I’d created just for him: fully glazed on the inside, but only glazed for an inch and a half, from the rim down, on the outside. The unglazed stoneware exterior of the mug’s main body acted as an insulator, keeping hot drinks hotter longer. On each mug, I incised the smiling-coffee-bean logo of the shop. What with the move from my old rented clay studio into my spiffy new digs, I was behind, and I didn’t want to let Carter down—he’d been a good customer for years.

I went into the workshop, which was unnervingly clean, since I hadn’t really used it yet, though soon enough it would be covered with a homey layer of fine gray dust. I hadn’t done more than slice a chunk of clay from a new slab when the bell over the front door jingled, announcing a customer.

I wiped my hands on my apron and hurried out into the shop. “Can I—” I began, then stopped. “You’re not a customer!” I said accusingly.

The young man who had just entered laughed, and ran a hand through his dirty-blond hair. “I could be,” he said. “I’m looking for a present for my girlfriend. What do you think she’d like?”

“Not pottery,” I said. “Anything but pottery.” I went around the counter and gave Brent a quick hug and kiss, both of which he returned enthusiastically, then leaned back, my arms around his neck. “Why aren’t you at work?”

“I am,” Brent said. “Sort of. Mr. Kapusianyk asked me to pick up something from the NatEx depot, and ‘as long as you’re down there, grab me a coffee at the Human Bean.’” He mimicked his boss’s distinctive Eastern European accent perfectly. “NatEx is a block that way,” Brent nodded to the right, “and the Human Bean is around the corner that way,” he nodded to the left, “so I’m in transit. I parked behind NatEx, so I’ve already put the package in the car. Good thing, too: it weighed a ton.”

“And here you are stealing from your employer’s time to pay your girlfriend a visit,” I said. “Naughty.”

“Not as naughty as I’d like,” Brent said ruefully. “I can’t steal that much time.”

I laughed.

He grinned. “Anyway,” he continued, “Mr. Kapusianyk won’t mind. Pretty sure he had a hunch I’d be stopping in.”

“I’m glad you did,” I said, the smile slipping away from my face as I remembered my early-morning visitor.

Brent clearly saw it go, because his own grin faded. “What’s wrong?”

I told him what had happened, two nights in a row now, and about my phone call to Policeman Phil. His face clouded with anger, which made me oddly happy. “I’ll stay here tonight,” he growled. “If he shows up again . . . ”

I gave him another hug. “Thanks,” I said into his shoulder. Then I pulled back, reluctantly; his body was warm and inviting. “But it’s not necessary. You’ve got the Talons game, and then you’ll have to take your Dad home, and you have to get up early for work. Phil said he’d have a cop keep an eye on the street. I’ll be fine. Anyway, he probably won’t show up with that storm coming.”

Brent blinked at me. “Storm?”

I sighed. “Not you, too. Yes, storm. Huge clouds. Black underneath. Coming from the mountains.”

He frowned. “I haven’t heard anything about a storm on the radio. And it plays all the time while we’re working.”

“You know how bad their forecasts are.” I untangled myself from him and tugged at his hand. “Come on, let’s head to the Human Bean, and I’ll show you.”

“Sure.”

He waited while I went back into the studio, pulled off my apron, and covered the clay I’d just cut with plastic wrap so it wouldn’t dry out. I came out again, and he followed me to the front door of the shop. “By the way, I don’t like the looks of those guys on the scaffolding,” he said as I paused to switch the LED sign in the window from OPEN to BACK SOON. “They make a move on you?”

“I’m too old for them.”

“You just turned twenty-nine.”

“And they’re like, twelve.” I opened the door, ushered him out onto the sidewalk, closed and locked the door behind us, then led him out onto the cobblestones of the pedestrian mall so I could turn around and see how the “twelve-year-olds” were doing. They’d made it all the way to the D, although at the moment it was hanging sidewise, so it looked like a goofy grin. I looked west again. The clouds now covered a third of the sky, and the mountains had vanished in their shadow and behind a wall of rain. “See?” I said to Brent. “Storm.”

He followed my pointing finger, looked for a minute, then shrugged. “If you say so. Just a few clouds. Doesn’t look very threatening to me. Nothing to interfere with the big game, at least.” He looked back at me. “If you’re worried about this guy in the street, you could come with me. Dad would understand.”

“No, he wouldn’t, not really,” I said. “And anyway, you know I don’t like lacrosse.” I took another look at the black clouds. Just a few clouds? Had everyone gone blind? I shook my head, and started walking again.

Brent fell in beside me. “Millions disagree with you.”

“I know.” Eagle River didn’t quite have 80,000 people, but there would be 30,000 in the stadium that night for the hometown Talons’ first-round playoff game against the Winnipeg Pooh-Bears. Millions more would watch on television. “Would you really give me a ticket and tell your Dad to stay home?” I said. “He’d kill you.”

Brent laughed. “Probably.”

“Well, sweet of you to ask. But you knew I’d say no.”

“Of course I did. But this way I get boyfriend points for asking, and son points for taking my Dad. Win-win!”

I laughed.

Now, if Brent had offered to take me to a moonball game, it would have been different, but since therewere only six teams, one each from the Indian, Chinese, Russian, British, Japanese, and American colonies, and all games took place on Luna, only the filthy rich could afford to attend the games in person. Prices on round-trip tourist excursions to the moon were falling every year, but they’d have to fall a lot farther before they landed in my price range, or Brent’s.

Kite-fighting was fun, too, but we only had a college team. Still, Brent and I had taken in a few matches—his Dad didn’t care for the sport.

“Is your sign going to be up today?” Brent said as we walked.

“I hope so. It’s a lot of letters.” I didn’t say anything more about the approaching storm that nobody else seemed worried about. Maybe I was overreacting. But as we reached the corner, I took another good look at the black shadows beneath those slowly approaching clouds, and saw a flicker of lightning.

No, I really didn’t think so.

We turned right onto 22nd Street. Ahead of us a half dozen round metal tables, painted in primary colors, dotted the sidewalk, with folding wooden chairs in the same bright shades arranged around them. About half were occupied by guys in suits and women in business dresses, and the other half by old guys with ponytails, wearing sandals and tie-died shirts, and women in flowing flower-printed dresses and floppy hats. It was that kind of town. (Cowboys like my early-morning visitor didn’t go in for fancy coffee shops much.)

The window to our right boasted the same goofily grinning cartoon coffee bean I’d soon be cutting into clay, although the one in the window also had stick legs and arms, and held an oversized coffee mug. Curly tendrils of steam rose from the mug, spreading to form the words “HUMAN BEAN.” Underneath the cartoon, on blackboard, was the day’s coffee bon mot: “God is a coffee drinker—He must be, to get all that work done in six days.”

I took Brent’s hand again. “Can you sit for a bit?” I asked. “Once we have our coffee?”

Brent squeezed my fingers. “I wish. But I really am just in transit. Also, I’m parked in a loading zone, and you know how . . . enthusiastic . . . the meter readers are around here.” He nodded down the street, where a guy in a bright-yellow vest was slipping a piece of paper under a pink Cornwallis PeoplePod’s windshield wiper.

I laughed. “I think they work on commission.” We passed under the shadow of Human Bean’s striped awning. Inside were more tables, the counter, and, at the far end, a small stage where bands of . . . let’s say, diverselevels of musical ability . . . played some evenings. In fact, there was a band due that night, something called the DNA Eruptions. Which sounded messy. But I’d probably check them out anyway, since even a band-of-dubious-quality beat sitting in my apartment binge-watching anime on StreamPix.

Besides, there was a good chance my best friend, Aesha Tripathi, would be free: we were having lunch together (also at the Human Bean, pretty much my home away from home) and I’d ask her then if she wanted to join me that evening. She’d just broken up with her boyfriend, an aspiring actor who had discovered he was gay during rehearsals for a Fringe show. (Well, that was the way he told it.) And in the evening, the Human Bean served beer (Moose Drool Brown Ale—my favorite!) as well as coffee. We could get comfortably sloshed together and stagger back to my place. And then we’d binge-watch anime on StreamPix.

Carter Truman, the ex-professional-lacrosse player who ran the Human Bean, grinned as he saw us approaching the counter, white teeth flashing in his lean black face. “Ah, my favorite couple,” he said. “Don’t usually see you this time of day!”

“Serendipity,” Brent said. “I just happened to have business at the post office, and look who I just happened to run into when I just happened to go into her shop.”

“Every day the world is full of amazing happenings,” said Carter. “The usual?”

“Large triple-sweet fat mocha latte for me,” Brent said. “Large skinny latte for my boss.”

I had felt myself gain five pounds just listening to the name of Brent’s preferred obscene concoction. “And for me,” I said primly, “medium French roast. No room.”

Brent and I looked at each other. “I don’t know how you can drink that stuff,” we said, in unison, an old joke, and Carter laughed again as he rang up the bill.

“Irreconcilable differences,” he said. “Are you certain the two of you are really cut out for each other?”

I leaned my head against Brent’s arm. “We’ll work through it,” I said.

Brent touched his cheek to my scalp. “We agree on the important things. ‘Life’s too short to drink bad wine.’ ‘A fool and his money make great drinking companions.’ That sort of thing.”

Carter’s grin flashed across his face again, and he turned away to work on our drinks. We moved to one side to let the people behind us reach the counter, where Carter’s place had been taken by Chloe, one of the endless series of interchangeable teenage baristas the Human Bean employed.

The door opened. A blast of cool air ruffled my hair and blew napkins off the cream-and-sugar counter. Startled, I glanced out the big front windows. A dust devil whirled past, bits of trash caught in the vortex . . .

. . . and beyond it, on the far side of the street, stood a man in a long black duster, face shaded by a cowboy hat, the wind whipping the hem of the coat around his high black boots.