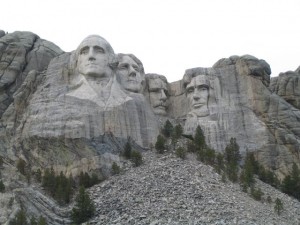

A recent trip to the United States provided me with an opportunity to see Mount Rushmore for the first time in more than 20 years…and marvel once again at what is both a great artistic work and a marvel of technological ingenuity.

The seed that grew into Mount Rushmore was planted by Doane Robinson, superintendent of South Dakota’s State Historical Society in 1923. He envisioned a series of giant statues of legendary Western figures. U.S. senator Peter Norbeck encouraged him to find a sculptor who could pull off such a challenge. He approached Gutzon Borglum, who had studied with Auguste Rodin in Paris and was a major American sculptor.

Borglum wasn’t interested in sculpting figures of only regional interest for his masterpiece. Instead, he, Robinson and Norbeck settled on four of the U.S.’s greatest presidents: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln.

You can’t sculpt giant figures in just any piece of rock. A series of peaks called the Needles, which Robinson had envisioned as the site of the sculptures, turned out to be made of rock too brittle. Instead, Borglum settled on 5,725-foot Mount Rushmore. Mount Rushmore’s granite outcropping appeared to have sufficient mass. As well, it had a southeastern exposure. That meant it had direct sunlight on it most of the day, ideal both for sculpting and for viewing. Most important, the granite appeared to be relatively free from fractures.

Borglum first created a model of the four presidents on a 1-to-12 scale, so that an inch on the model represented a foot on the cliff. To transfer the model to the mountain, he placed a metal shaft upright at the center of each head on the model. Attached to the base of the shaft was a protractor, marked in degrees, and a horizontal ruled bar that could pivot around the metal shaft to measure the angle of each feature from the central axis. Attached to the bar was a weighted plumb line that could slide back and forth on the bar to measure each feature’s distance from the central point. It could also be raised and lowered to measure vertical distance from the top of the head.

All Borglum had to do to place any point on the mountain exactly as it was on the model was to multiply those measurements by 12, then use them to set identical pointing mechanisms (but 12 times larger) on the mountain.

Originally, Borglum ruled out the use of dynamite in the sculpting process. But so much weathered rock had to be removed to reach the solid granite–in total, 450,000 tons–that he soon changed his mind.

First, enough rock was blasted away to create egg-shaped volumes of granite for each head. After that, skilled blasters was able to dynamite rock to within a few inches of the desired measurements. Next, workers suspended in seats on the end of cables used pneumatic drills to honeycomb the granite, drilling closely spaced holes to almost the depth of the final desired surface. The excess rock was then chiseled off. Finally, the drill holes and lines left behind were gently (relatively) knocked away with pneumatic hammers. The final result was a smooth, white surface.

Borglum supervised every step, making changes in his design as necessary. For instance, Roosevelt’s face wasn’t initially intended to be set so much further back than the others; Borglum had to make that adjustment when it turned out the rock wasn’t solid enough any closer to the surface. Similarly, Jefferson’s head was moved from Washington’s right to his left side, because there wasn’t enough rock to complete the figure as planned.

One of the sculpture’s most amazing features is the eyes. They seem to sparkle with life, instead of being merely dead holes in the granite. The pupils are actually shallow recessions with projecting shafts of granite. From a distance, that shaft of granite tricks us into thinking we’re seeing a highlight off of an actual eye, and brings the gazes of the presidents to remarkable life.

Borglum died in March of 1941. He lived to see all four heads dedicated, but his son continued refining the sculpture to its present state until October of 1941. The final dedication wasn’t held until 1991.

Mount Rushmore today is one of America’s greatest national monuments. It’s both an astonishing work of art–and an astonishing feat of engineering and technology.