Here’s my latest column for the Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild’s newsletter Freelance…

***

K.W. Jeter – Photo by Gemnerd – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia

They’ve become a fixture at science fiction conventions: people wearing goggles, leather coats, high laced boots and aviator caps, carrying strange devices of glass, brass and leather. They look old-fashioned and futuristic at the same time.

They’re aficionados of a sub-genre of science fiction and fantasy known as steampunk, one of the odder sub-genres to come along in a while…and one that has proven remarkably long-lived.

Way back in the 1980s, the hot movement in SF was cyberpunk, of which Canada’s own William Gibson was one of the top practitioners. Cyberpunk was all about tech-savvy geeks in mirror shades hacking and surfing computer networks. Steampunk has pretty much nothing in common with it—except for the name, coined by science fiction writer K.W. Jeter.

According to Wikipedia (a source I consider suspect for a lot of things, but not when it comes to geek history; there are an astonishing 71 references listed for the article on steampunk, a good place to start if you really want to steep yourself in the subject), Jeter wanted a general term for four novels that all took place in a 19th-century setting and imitated the conventions of the SF writers of that century, such as H.G. Wells and Jules Verne: The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers, Homunculus by James Blaylock, and Jeter’s own Morlock Night and Infernal Devices.

In a letter to Locus (the science fiction newsmagazine), Jeter wrote, “Personally, I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing, as long as we can come up with a fitting collective term…something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like ‘steampunks,’ perhaps…”

His prediction proved perceptive: in 1990 William Gibson turned from cyberpunk to steampunk with The Difference Engine, written with Bruce Sterling, about an alternate Victorian era in which the steam-powered mechanical computer proposed by Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage was actually built, and ushered in the information age a century early.

(Not that any of those novels were the first example of the sub-genre. There were numerous novels with steampunkish elements before those, and who can forget the 1960s CBS TV series The Wild Wild West, featuring U.S. secret agent Jim West as a “James Bond on horseback,” armed with all kinds of technological tricks and gadgets and facing villains similarly equipped?)

These days, “steampunk” covers a lot of ground. There’s historical steampunk, set in a recognizable historical period (or alternate version thereof), typically post-Industrial Revolution but pre-electricity, resulting in lots of steam-powered or clockwork gadgets. There’s also fantasy steampunk, which incorporates, not just old-fashioned technology, but elements of magic. (Jeter’s own Morlock Night is about an attempt by Merlin to bring back King Arthur to save 1892 Britain from an invasion by the Morlocks of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine future.)

A third sub-sub-genre is future steampunk: stories set in the future whose technology developed in a different way, one that involves a lot more brass and rivets. (And airships! Nothing says steampunk like airships.)

Then there’s the sub-sub (possibly sub-sub-sub) genre of “gaslight romance” or “gaslight fantasy,” which tend more toward the supernatural, drawing inspiration from Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde, Jack the Ripper, and so forth.

What’s striking about steampunk is its staying power. Although we live in a cyberpunkish world, where anonymous hacking groups regularly steal data, as a sub-genre cyberpunk is stuck on the blue screen of death, while steampunk chugs along undaunted.

The reasons for that formed the subject of a recent “Mind Meld” at SF Signal, a website that regularly asks writers and critics to answer questions on SF-related topics. Jeff Vandermeer, an editor and author who rarely writes steampunk himself but writes about it quite a bit, gave what I thought the best explanation: steampunk persists because it has become its own sub-culture, focused not just on fiction but on the aesthetic as a whole (hence those costumers mentioned at the beginning of the column).

When the boilers of steampunk fiction begin to lose pressure, the subculture stokes the fires again, so that, as Vandermeer writes, “The subculture reanimates the impulse to create steampunk fiction, the fiction energizes the subculture.”

The cross-pollination among websites, books, magazines, artists, sculptors and costumers creates an atmosphere in which “steampunk” books sell well…which encourages publishers to publish more steampunk books.

The result, Vandermeer says, is that “steampunk is rapidly creating a safe haven for very, very interesting material that might not otherwise enter the world through commercial publishers, or even through indie publishers…It isn’t the bleeding edge in terms of innovation in fiction by any means, but it is in general practical, more and more progressive, durable, and beautiful.”

The result, Vandermeer says, is that “steampunk is rapidly creating a safe haven for very, very interesting material that might not otherwise enter the world through commercial publishers, or even through indie publishers…It isn’t the bleeding edge in terms of innovation in fiction by any means, but it is in general practical, more and more progressive, durable, and beautiful.”

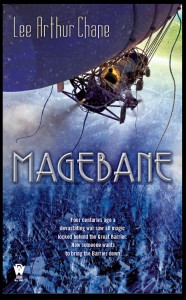

And let’s face it, airships and goggles are cool. Which is why I have both in my next book, Magebane, even though it’s fantasy, not science fiction.

What can I say? Steampunk is in the air, and even I am not immune.