[podcast]https://edwardwillett.com/wp-content/uploads//2011/11/Viking-Sunstone.mp3[/podcast]

The World Fantasy Convention in San Diego, which I attended a couple of weeks ago in my guise as fantasy author Lee Arthur Chane, had as its theme “Sailing the Seas of Imagination.”

The World Fantasy Convention in San Diego, which I attended a couple of weeks ago in my guise as fantasy author Lee Arthur Chane, had as its theme “Sailing the Seas of Imagination.”

It’s a shame the topic of this week’s science column didn’t hit the news until after that convention ended, because really, it sounds like something straight out of a fantasy novel set on the high seas.

The Viking sagas speak of a “solarsteinn,” or sunstone, which, when held up to the sky, could reveal the presence of the sun even on overcast days or when (as it so often is even here in Saskatchewan, much less at Viking latitudes) it is below the horizon.

This sounds like magic, but of course (pace World Fantasy Convention) in real life there’s no such thing. So unless the sunstone was a myth, there had to be an explanation for it.

One long-running theory has been that the sunstone was a block of refractive crystal that could reveal the direction of the sun when human eyes couldn’t—but there’s never been any hard proof.

Just this month, however, an international team of researchers, led by Guy Ropars of the University of Rennes in Brittany, France, published a study in the Proceedings of the Royal Society A in the U.K., which offers experimental and theoretical evidence.

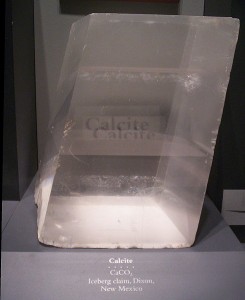

Specifically, they argue that Viking sunstone was simply transparent calcite crystal, a.k.a. Iceland spar.

Calcite is one of the most common minerals on Earth. Its crystals come in many different shapes, and in white, gray, yellow, pink, light green, brown, red, violet, blue and black.

But it also comes in colorless, ice-clear form, and in that form it’s known as Iceland spar (the name alone an indication that the Vikings would have had no trouble getting their hands on it, although we call it that because of the prodigious quantities that came out of Iceland’s Helgustadir Quarry and Mine from the mid-17th right up until the 20th century).

Iceland spar exhibits a fascinating characteristic known as double refraction.

Refraction is the bending of light as it passes through a transparent material (think of the way a pencil looks broken when you stick it in a glass of water). But Iceland spar does something more: it blocks all of the light entering it except for the waves vibrating in two specific planes, perpendicular to each other. These two differently oriented beams of light travel through the stone at slightly different speeds, which in turn means they emerge in slightly different locations. As a result, if you view, say, a line of text through Iceland spar, you’ll see the text twice.

Even on a cloudy day, or with the sun below the horizon, the sky is filled with concentric rings of polarized light, with the sun at their center. Passing light from the sky through calcite produces two offset images, their brightness relative to each other depending on their polarization. By turning the crystal until both images are equally bright, you can determine in what direction the sun must lie.

To test this, the researchers locked a chunk of Iceland spar into a wooden device that beamed light from the sky onto the crystal through a hole, projecting the resulting double image onto a surface. By changing the orientation of the calcite until the projections of the light from the sky were equally bright (and the human eye is extremely good at determining relative brightness), they were able to calculate the position of the sun on an overcast day (which they already knew by other means) within one degree of accuracy.

No sunstone has yet been found on the wreck of a Viking ship, but a piece of Iceland spar was found aboard an Elizabethan ship sunk in 1592, suggesting that even after the Vikings were long gone, their sunstone was still in use. And since, as the researchers note, even one of the cannons on that Elizabethan ship represented enough iron to mess up a magnetic compass by as much as 90 degrees, on a cloudy day the use of this ancient “optical compass” might have made the difference between coming safely to shore and running aground.

A stone you hold up to the sky to locate the sun? It’s not magic at all: it’s pure technology, made possible by the laws of physics.

And while that might disappoint fantasy author Lee Arthur Chane, it fascinates science columnist Edward Willett.

The photo: Large crystal of Calcite on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC.